Part I — Neuroplasticity depends on healthy organs: insights from science and Japanese meridian yoga

This article was published by Yoga For Good Foundation. Click on the image below to go to the YFG article, or read the full text below.

Comments:

Thanks for sharing. As a Zen Shiatsu Therapist and Yoga Therapist, I found this to be a great reflection on these philosophies and practices. — Rebel Tucker, yogarebel.com.au

Most of us go through life with a general sense that the brain and body affect each other, but rarely stop to think about how deep that connection really runs. The reality is, there’s far more happening under the surface than we know.

At Yoga for Good, we spend a lot of time exploring what supports people’s wellbeing in a real, practical sense. Understanding the link between how the body functions and how the mind works is a huge part of that. As a neuroscientist and an experienced yogi, I find it particularly fascinating. In this article, we’ll look at how neuroplasticity depends on the health of your organs, drawing on both science and Japanese Meridian Yoga.

Recent science on neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to adapt to changes in our environment. The purpose is to ensure that we survive, and ideally, thrive. For decades, the scientific research into neuroplasticity focused almost entirely on the neurons in the brain. More recently, the research has shown that other cells in the brain, known as the glial cells, are far more plastic (i.e., changeable) than the neurons. (This is what I did my PhD on and worked on as a Research Fellow. You can read my papers here.)

Even more recent research is now revealing how the gut intricately orchestrates neuroplasticity in the brain. Importantly, gut inflammation can throw the delicate balance in the brain into chaos and be a leading risk factor (or possibly, cause) of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

We know from science that neuroplasticity is essential for all aspects of learning, memory, executive function, and well, life. And we are now beginning to appreciate the central, pivotal role that the gut plays in brain function, mental health, immune function, digestive function (of course), and all the other major body systems.

Inflammation disrupts neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity is a process of the neurons and glia changing both their morphology (structure or shape) and their expression of neurotransmitters, receptors and other molecules (function). This happens from moment to moment in a tightly integrated interplay of interdependent processes.

Scientists used to believe that the brain was protected from events in the rest of the body by the ‘blood-brain barrier’. But research is increasingly demonstrating that this barrier does not prevent the state of the body from being communicated immediately to the brain via the nerves and blood.

It turns out that the cells and chemical signalling molecules of the immune system have a reporter pass for crossing the blood-brain barrier. And when there’s gut inflammation, not only is there immune signalling to the brain via the blood, but also the vagus nerve sounds the alarm by communicating the information of distress directly to the brain. The net effect of inflammation in the body, particularly if it’s systemic (widespread) or gut-derived, is that the inflammatory processes in the brain are also activated.

The glial cells throughout the brain are all immune-competent. This means that immune signalling disrupts them from their normal regulatory processes, such as controlling neuronal firing, consolidating memory, directing oxygen and nutrients to active neurons, and producing new neurons (to name a few). Instead, activated glial cells radically and rapidly change their shape and switch from producing neuroregulatory molecules to immune molecules.

In effect, the regulation of neuronal function, including neuroplasticity, is disrupted in the presence of neuroinflammation. And neuroinflammation will be present if there is inflammation in the body.

Ancient knowledge on neuroplasticity from Japanese meridian yoga

What does Japanese meridian yoga have to say that we

don’t already know from science? The short answer: a lot.

The medium-length answer: the health of the organs and

their associated meridians is what determines the

functioning and adaptability of the brain.

The long answer: here it comes; it’s exciting and revealing,

so hang in there. Japanese meridian yoga (also called

Japanese yoga therapy and Okido yoga) is based on the

5-element theory of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

These 5 elements are energies that all matter is composed

of in varying amounts.

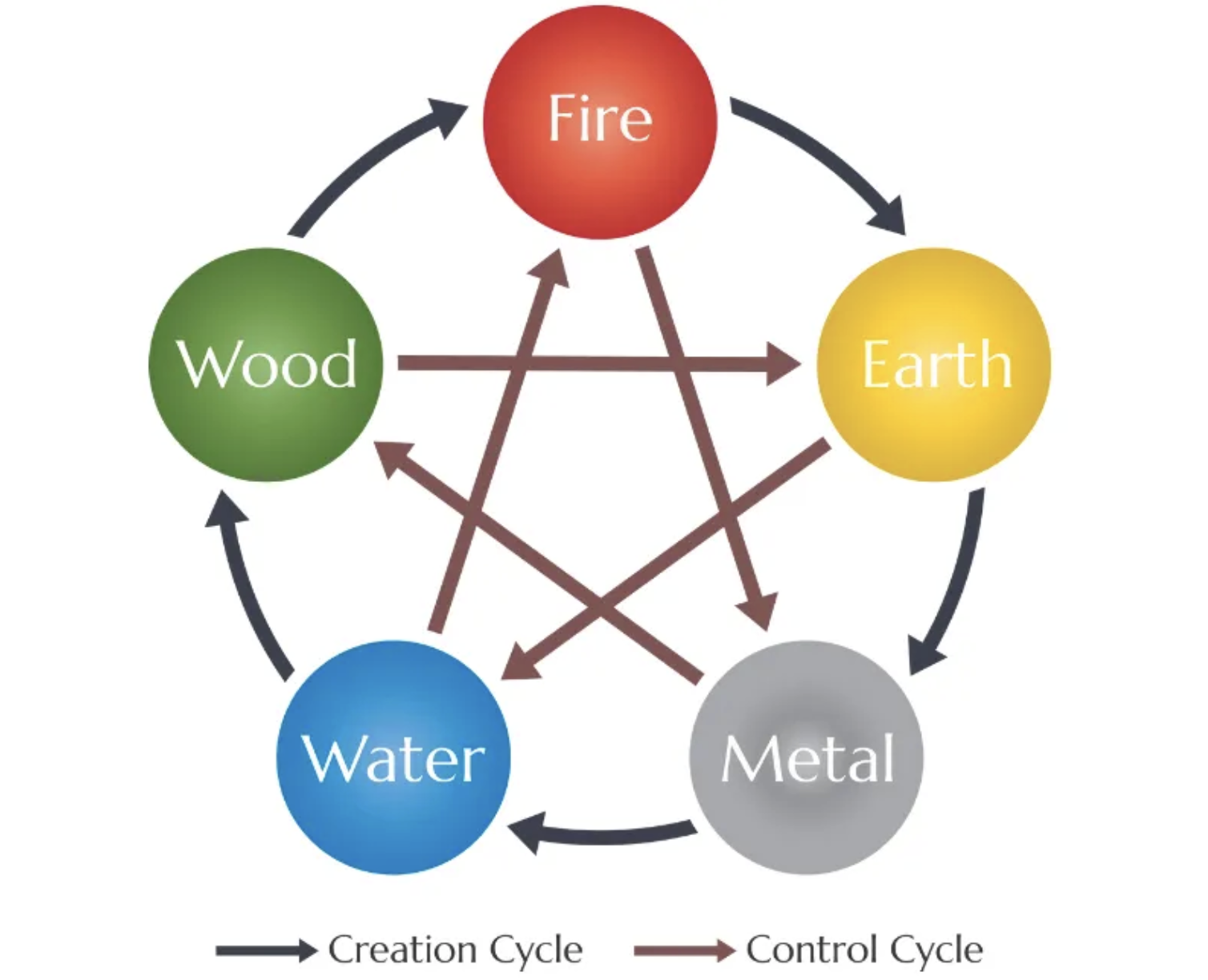

The whole of nature, and its cycles, is created by the patterns of interaction between the 5 elements — Water, Wood, Fire, Earth and Metal. There’s a creation cycle and a control cycle, which together keep life in a never-ending state of flux that tends towards balance (see Figure). The creation cycle is the easiest to see in nature as it forms the seasons — Water is winter, Wood is spring, Fire is summer, Metal is autumn, and Earth is late summer and the transitions between the seasons. In TCM, and the Daoist philosophy it’s based on, a central concept is that the human body is a smaller version of the energy of the cosmos and vice versa. The sayings ‘as macrocosm, so microcosm’ and ‘as above, so below’ come from other ancient traditions and sum up the concept succinctly. Essentially, what it means is that whatever is going on in nature is also going on in our bodies (and vice versa). And from the ancient wisdom and knowledge of TCM and 5-element theory, we know that whatever is going on in our body is going on in our brain. The brain is like a microcosm to the body’s macrocosm (or is it the other way around?).

In other words, what all these esoteric concepts mean is that the brain is fundamentally changeable, or plastic, because it’s intricately connected to and part of the body. Even the mind, which is not the brain, is dispersed in the body. The ‘Heart-mind’ is a concept that the Japanese call ‘Kokoro’, and in yoga has at least four levels, most closely represented as ‘Buddhi’, or perhaps ‘Citta’, which are housed in both the heart and brain.

So, the body, including the brain, is in a constant state of 5-element flux. The brain–body cannot be anything but plastic. The only reason science took SO long to discover this fact was because of the neuro-centric model of the brain that predominated throughout the 20th century at the expense of the synergistic neuro-glia model. The neuro-glial model was originally proposed in 1887 by Ramón y Cajal but was rejected due to the scientific dogma of the day — that the nerve cell is paramount and unchangeable, fixed for life — which we now know to be incorrect. Rather, the neuro-glia model is correct, more so than Ramón ever likely imagined.

The meridians influence the emotions

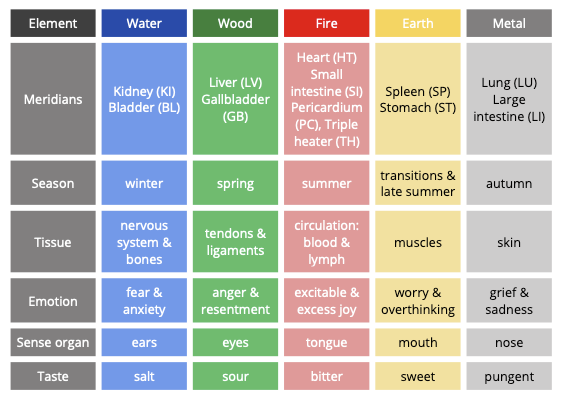

Each element is associated with

a season in which that element

or energy predominates. Likewise,

each element is associated with

a pair of meridians, organs, bodily

tissues, a colour, emotions and

so on (see Table). All the meridians,

except the Heart meridian,

terminate or begin in the head.

All the meridians, including the

Heart meridian, influence brain

function. Note that the heart’s

bioelectromagnetic field is many

times greater than that of the

brain and has a strong influence

on the entire body, particularly

the brain, and on the energy, mind and emotions of those around us.

We can better conceive of how the meridians might influence the brain by understanding that the energetic link between the body and mind is the emotions. Emotions are the result of thoughts in the brain. Thoughts create energy in the body that is experienced as felt sensations and emotions. Negative thoughts produce negative emotions, and positive thoughts create positive emotions. In addition, when any of the meridians is imbalanced, it will create a negative emotion through its effect on the brain. This process — thought-derived emotions and body-derived emotions — is cyclical and inextricably linked, one influencing the other in a never-ending cycle. (But it’s not all doom and gloom — more on that later.)

Connect with your true self through the transformative power of yoga

This connection between body, mind and emotion reflects yoga’s deeper purpose of helping us return to our true selves. In the next article, we’ll explore what happens when the meridians fall out of balance and how that shapes the brain in everyday life.

By Dr Adele Vincent